By CRISTINA JANNEY

Hays Post

Angela Bates, executive director of the Nicodemus Historical Society, gave a presentation Saturday in Hays on Nicodemus and the role of African American women through history.

Bates spoke to the Courtney-Spalding Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

She is a descendant of the first settlers in Nicodemus, who came to Kansas in 1877. Nicodemus is the last and only remaining all-African American settlement west of the Mississippi. At its height, the community had about 600 residents, but the population declined after the railroad decided not to route through the town.

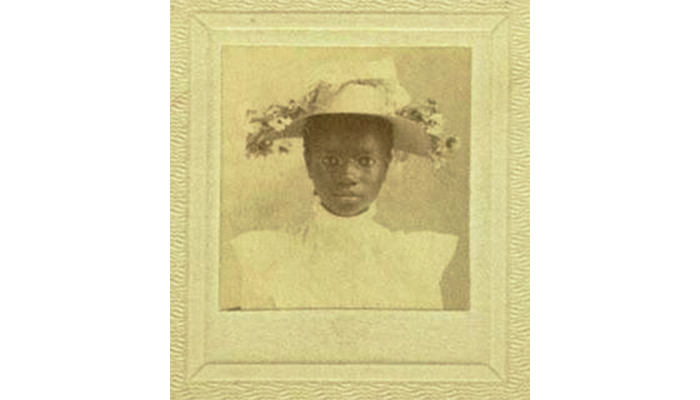

Bates has done extensive research on Nicodemus. In 2012, she published a book with more than 200 historical photos. It is still available in Nicodemus, which Bates was instrumental in getting declared a National Historic Site.

To understand African American culture today, Bates said you have to go back to the slave culture in the South.

“Women did not have choices during slavery,” Bates said.

African American women worked in the fields or in the master’s house. Women who were older or not as physically capable raised the children during the day. They referred to them as aunties or grannies.

This is why women or men that are family friends are often still referred to as aunts or uncles in black culture, even though they may be no blood relation. It is a term of respect, Bates said.

Some of the slave children would be assigned to the master’s children. They would help take care of the children, empty their chamber pots, fan them, help them dress and maybe even play with them.

By the time the slave children were 12, they were assigned adult jobs.

“You did not have any control of what was going to happen to your kid,” Bates said. “If they wanted take the kid and take her to the house like in the movie ‘Queen’ after she had the child by her master, the master could say ‘I want the child to be raised in the house.’ ”

Bates said part of the psychology of controlling the slaves was divide and conquer. The slave owners fostered division between house and field slaves as well as division among light-colored slaves and darker-colored slaves.

Yet, any amount of African blood in a person in the South, no matter what their appearance, meant they were regarded as black.

“If you were dark and had kinky hair, you were considered less than a mixed blood that would have lighter complexion and more white features and straighter hair,” she said.

“So when Emancipation comes, the mixed bloods that were living in the house and some of them may be living in quarters, they are shunned on both sides of the fence. The full bloods have been taught to shun them because they think they are better, and that still has psychological effects on African Americans today. We have intraracial prejudice against each other along those same lines.”

Also after Emancipation, women begin to have choices not only about their own lives, but the rearing of their children.

“Freedom affords you an opportunity to have a choice,” Bates said. “You can pick who you want to be married to. You can decide what your children’s names are going to be. Many people change their names right after Emancipation.”

In some cases, brothers chose different surnames. Bates gave the example in Nicodemus of the Wellingtons and Weltons. There were three brothers all Wellingtons, but one changed his name to Welton.

“If you were looking at genealogy or even the census, you would not know,” she said.

In another case, a woman was pregnant at the end of the Civil War and decided to give her child the surname Taylor, instead of the name of her plantation owner. There were brothers and sisters in that family as well who had a different surnames.

Freedom in Kansas meant choices, your children weren’t going to be sold away from you and it was an end to a violent life.

“Imagine you have a child and you love that child and you watch that child grow, and then he does something that he wasn’t supposed to do and he gets beat on the public pole,” Bates said. “You don’t have any choice, and they make you stand there and watch your child get beat.”

A new psychology took hold after African Americans were freed. Bates summed up with the phrase “We rear our daughters and we love our sons.”

Bates said African American women are very independent and opinionated.

“We had to be,” she said. “How can you depend on a man who you may have jumped the broom with, but he doesn’t have any control over himself? So how can I rely on him? Coming out of slavery, African American women relied on themselves. So in the culture we raise our daughters to be independent.”

Women also continued to rely on the “sisterhood,” friends and other women in their community, just as the women in slavery relied on the aunties and grannies to raise their children.

In a white society, black mothers felt sons, who might struggle to find jobs and face other prejudices, needed their support, Bates said.

“We are all suffering from post-slavery trauma,” Bates said referring to both white and black cultures.

Bates said the relationships between black and white women can still be strained.

“Back in the ’60s I would be called a Tom, an Uncle Tom,” she said. “That would be someone who embraced relations with white people. I have found just being a human being that people are people, no matter what. There are people who are black that I would not want to be around.”

At the end of her presentation, Bates was honored with the DAR Women in American History Award for her work to preserve African American history.

Bates also serves as a speaker for the Kansas Humanities Speakers Bureau, who sponsored her talk Saturday. She is a member of the National Parks Conservation Association and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Bates received the Kansas Sampler Foundation’s “We Can” award (1993), the Brown Foundation’s award for excellence (1994), the Outstanding Contributions award (1996) from the Kansas Humanities Council, the African-American Preservation Hero award (1996) from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the Woman of Distinction award (1997) from the Kansas Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Committee of Topeka for her work in preserving African American history, and, more recently, the 2012 Kansas Trail Blazer Award. (Bio information courtesy of the University of Kansas).

Learn more on Nicodemus from the Kansas Historical Society or the National Park Service.