By CRISTINA JANNEY

Hays Post

Vietnam War Veteran John Musgrave thinks America has forgotten lessons of the Vietnam War.

A decorated Vietnam veteran, John Musgrave will be welcomed to Fort Hays State University’s campus by the Department of Political Science at 7 p.m. Wednesday in the Memorial Union Black and Gold Room to share his experiences and memories from serving in the Vietnam War.

Musgrave has been featured in a 2017 documentary, “The Vietnam War,” produced by Ken Burns and Lynne Novick.

Even after decades of speaking and advocating for veterans, Musgrave said the documentary was still important for millions of people to understand the war, what happened its consequences even to this day.

He said the country needs to remember the sacrifice of tens of thousands of young Americans, who believed in what their country was doing or not believed in serving their country.

“The country’s attitude when we came back was not positive,” he said. “If they remembered, they tried to remember as only misfits, criminals, drug addicts, crazies. I great many of us still carry a great deal of bitterness over the way we were treated when we came home because we gave everything we had. Nearly 60,000 of us did give everything.”

When he came home from Vietnam, Musgrave was called a war criminal and a baby killer. In Vietnam, veterans were portrayed as criminals.

“It was a poisonous atmosphere. It was ridiculous and it’s why tens of thousands of Vietnam veterans came home, shoved their uniforms in their closets — or worse threw them in the trash — and never told anybody, even their own children, that they served their country honorably in a war.”

Many veterans lived with their service as a stigma, which lead to more veterans dying of suicide after the war than died in the war, Musgrave said.

“That is an indictment of our society,” he said. “They felt so alone.”

Treatment of Vietnam veterans has improved over the years. Today, strangers thank Musgrave for his service and pay for his dinner.

“I am flabbergasted when that happens because I still expect people to call me a war criminal, but when I turn around and look down that long road to someone coming up to me and thanking me for your service, I see it strewn with tens of thousands of bodies of forgotten men who lost everything. I can’t allow that to be forgotten.”

Musgrave also wants Americans to remember how slippery the slope is on foreign policy. He says the United States chose to support a dubious and anything but democratic Vietnamese government.

The buildup of U.S. troops in Vietnam grew without the public really realizing what was happening.

He said there are similar disconnects today.

“I am talking to kids who have no memory of the towers coming down. They have only seen pictures of it, so they are fighting in a war now they have no living memory of,” he said.

“I was in Vietnam 52 years ago, I think America has tried very hard governmentally and on a society level not to learn anything from it. They prefer to forget it. It is a bad memory. We lost or at least we didn’t win. … I think we have repeated the same mistakes since, getting our children involved in no-win wars with no end in sight.

“Yet the specter of Vietnam hovers over us almost shouting, ‘Notice me! Learn from me!’ And I don’t think we have. I think we are working hard not to.”

The U.S. has also forgotten it left hundreds of living American prisoners of war in Laos and Vietnam in the hands of the communists.

“The government knew about them, had their names, had their locations and wrote them off because they decided they were just too inconvenient to save. You can’t call that peace with honor. For many Vietnam veterans, that is an open festering wound to know that the war doesn’t end until everyone comes home and that we mattered so little to the government of the United States that it would do that. …

“That was a conscience decision made by Nixon and Kissinger,” he said. “I could curl your hair with the information I have on that.”

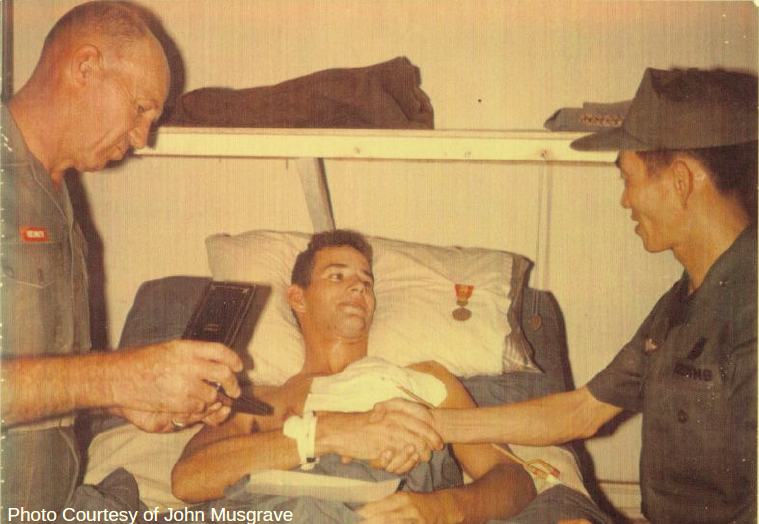

Musgrave was born in Missouri in 1948 and enlisted with the Marine Corps at the age of 17. He served with Delta Company, 1st Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division in Quang Tri Province, Northern I Corps, during the Vietnam war for 11 and a half months before being permanently disabled by his third wound. He was eventually medically discharged.

His Marine Infantry Battalion lost more men than any other battalion in the history of the Marine Corps. They are referred to as the Walking Dead.

Musgrave was medically retired from the Marine Corps as a corporal in 1969 after a long hospitalization. He still suffers from some physical disability from the wounds he suffered in Vietnam.

He also has suffered from PTSD since his time in combat. His wife to had to explain to his children why he slept with a night light. He was afraid of the dark.

Musgrave was only 17 when he joined the Marines. He said he was terrified.

“You’re damn right I have nightmares. It was horror on horror.”

He described the North Vietnamese Army as vicious.

“I am alive today because buddies of mine gave their lives in attempts to rescue me when I was wounded. The guy that shot me used me as bait, because he knew that Marines never left a wounded Marine on the field, so he left me as bait. He knew as long as I was screaming, my buddies would keep coming. I don’t have the right to allow them to be forgotten.”

Musgrave says mental health services for active duty service personnel and veterans is getting better, but it still is not enough. He said young soldiers are being used up by repeated deployments to combat zones.

When he first came home from Vietnam in 1968 and 1969, he was sent home periodically as he was recovering from his injuries. He was asked to speak to local groups about the positive role of the military in Vietnam. He was being asked questions from student groups that he couldn’t answer.

“The more I read … the more I discovered reasons for us not to be there,” he said. “It was heartbreaking. I gave everything I had for that cause, but I was still a Marine and I won’t say a word about it.”

He felt conflicted, but he wanted to feel he was still supporting his buddies who were now serving their second tours in Vietnam.

“I am spewing things that I don’t believe in any more. In fact, that I knew were bullshit, but I felt as if I had to do it to be loyal.”

The U.S. invaded Laos and Cambodia. Students were killed at Kent State. Nixon began a troop withdrawal, but American soldiers were still dying daily. Finally, he said he couldn’t do it any more.

“I realized I didn’t have the right to sit at home and drink and cry in my beer when my buddies were over there fighting for nothing. … I realized what I owed my country was the truth.”

In 1970, he joined and served in a leadership role with the Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

“I realized that I kept my mouth shut so long, because I was a good Marine, but now it was time for me to be a good citizen and good citizens do not stay silent.”

As he speaks to young people across the nation today, Musgrave echoes that hope for today’s youth.

“I tell them all I want them to do is their duty as citizens and their No. 1 duty is as citizens is to make informed decisions and to ask questions. If they see anyone doing anything that is not in the best interest of their country, it is their patriotic duty to stand up and say no. On the other hand, if they see their country doing exactly what it should be doing, then they should stand up and support it. Silence is always consent whether you intend it to be or not.”

Musgrave has written three books of poetry, including “Notes To The Man Who Shot Me,” which won the Robert A. Gannon Award for Poetry by the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, and he helped co-author “The Vietnam Years: 1000 Questions and Answers,” with Mike Clodfelter.

Musgrave now lives in Baldwin City with his wife.

Pi Sigma Alpha, the political honors society at FHSU, is sponsoring the event.

Musgrave’s talk is free and open to the public.