By CRISTINA JANNEY

Hays Post

The Poor People’s Campaign made a stop in Hays last Sunday advocating for rights for the disabled, affordable health care and an end to the war economy.

Nathan Elwood, Fort Hays State University librarian and Poor People’s Campaign volunteer, introduced speakers who were local residents and from the national movement.

“We are here to talk about poverty. We are here to talk about economic and social injustice,” he said.

“These aren’t easy comfortable topics to talk about. In fact, from a young age we are taught not talk about these things. We are told it is impolite to talk about money. We are told if we are struggling, we should grin and bare it. We are told not to burden others, but avoiding discussions of the problems we face as a community won’t make those problems go away.”

In Hays, 19.5 percent of residents live below the poverty line, which is higher than the 13 percent national average. Indicators predict the poverty rate will continue to rise despite low unemployment in the area, Elwood said.

Claire Chadwick, a campaign volunteer, is a pastor with a master’s degree, but she is a low-wage worker. She has been poor all of her life. Her father was homeless for a time and they lost their home in the mortgage crisis.

“The reason that I got involved with the Poor People’s Campaign is because it taught me that losing our house in the mortgage crisis — that being a low-wage worker even with a master’s degree — that it wasn’t something that I was doing wrong.

“There isn’t something inherently the matter with me. It is not a character flaw. It is not an accident, but it is a part of a larger system.”

Work can be way out of poverty for disabled

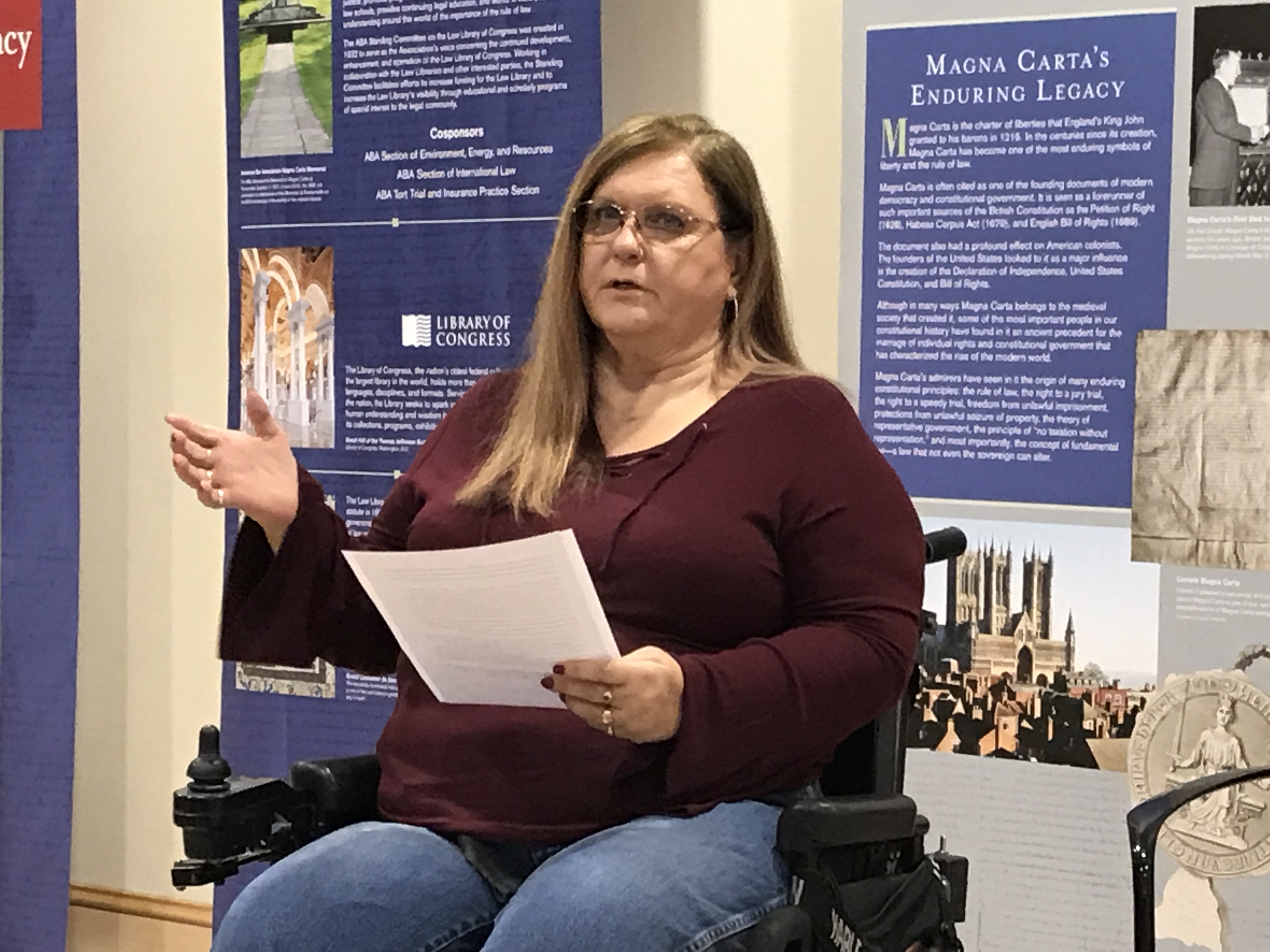

Ellis County resident Lou Ann Kibbee was disabled 42 years ago. She now works as an advocate for the disabled at the local, state and national levels. She is currently employed at the Skilled Resource Center.

For the first 16 years after her injury, Kibbee received a variety of assistance from government agencies, including Medicare, Medicaid, HUD and Social Security Disability.

“I learned early on that society did not expect me to become employed, because I have a disability” she said.

She was discouraged repeatedly from seeking employment, even by government workers who warned her she would lose her benefits if she got a job. Yet, her disability check was only $570 per month.

Her medical care was not equal to that of private insurance, and although most people on disability also receive food assistance, it is not enough to eat healthy, she said.

Yet, she compared leaving disability for a job to jumping out of a plane without a parachute.

“But I did go to work, because I knew that was my only possibility of getting out of poverty,” she said. “I knew that I needed a pretty good paying job to support myself and a college education to do that and compete with other applicants.”

Today, it takes Kibbee and her husband’s combined income to pay her extensive medical expenses. She pays $14,000 per year alone for attendant care services.

Not surprisingly, as of 2017 only 46 percent of disabled Kansans of working age were employed.

“We try to continue to educate people with disabilities about going to work, but there needs to be more incentives, so that they can afford to make that move,” Kibbee said. “Employers in communities need to be educated more about the capacity of people with disabilities to become employed in integrated competitive employment.”

Thousands of people with disabilities are in nursing homes or institutions waiting for in-home services, because in Kansas in-home services are optional.

“It should be a civil right for anyone with a disability to live in their homes and communities just like anyone else,” she said. “When we live in the community, we are able to earn and spend money, get educated, have families, pay taxes and contribute to our communities.”

Skyrocketing medical expenses

Laura Allen, First Call for Help client services specialist, talked about her personal experiences struggling to pay for medication for her son. Allen is a single parent of three children. Two years ago, her son had to have a heart transplant because of a congenital heart defect.

After his last round of rejection, he came home on two kinds of insulin. The bill for less than one month of insulin was $6,500. His anti-rejection medication was another $4,000.

Vera Elwood, a FHSU master’s student, said she and parents planned from the time she was 12 years old and was diagnosed with diabetes to provide for her insulin when she graduated college. The fear was that she would be without health care until she could find a job.

When the Affordable Care Act passed, which allowed young adults to stay on their parents’ health insurance until they are 26, Vera’s whole family cried together. Today, Elwood is covered under her husband’s health insurance. However, she said affordable health care and insulin is still a matter of life or death for her.

“All of these changes that are coming up — getting rid of pre-existing conditions, getting rid of mandatory health care, not expanding Medicaid — these things have real, real impact on 12 year olds who are planning to not die when they graduate college,” Vera said.

Allen added doctors told her if her insurance would not cover the cost of her son’s anti-rejection medication, the doctors were unwilling to do the transplant.

“Because it was a wasted organ without the money and medications to go along with the transplant,” she said.

Working and uninsured

Twenty-four-year old college student Heather Letourneau is an attendant care worker in Hays. She has no health insurance. It is not provided by her job regardless of the number of hours she works.

“From the outside looking in, it appears that I should have no trouble paying for health care because I make well above minimum wage. When I was working 40 hours a week, I was only getting $1,200 a month, which paid my bills. It did not pay for groceries or gas,” she said.

She noted she cut out all non-necessities and still struggles to pay her expenses.

Letourneau advocated for higher wages and Medicaid expansion to help her and other attendant care worker who do not have insurance.

Veteran against the war economy

Christopher Overfelt served in the Topeka Air National Guard for nine years as an aircraft mechanic. During that time, he deployed to Iraq and Turkey.

Overfelt, who is member of Veterans for Peace in Kansas City, spoke about how the U.S. military policy harms poor people in the U.S. and around the world.

“In 2009, I deployed to Turkey and Qatar, and participated in the destruction of two sovereign nations — Iraq and Afghanistan. In Qatar I repaired and maintained the aircraft that refueled the bombers on their way to sew death and destruction in Iraq,” he said.

“Neither of these countries will likely recover from that devastation in my lifetime,” he said. “Nothing I can do will make up for the hundreds of thousands of Afghan and Iraqi men, women and children killed in these wars.”

He said he had no idea when he joined the military that the Department of Defense has never completed an internal audit of its spending despite it being mandated by law.

“It doesn’t know how much money it is spending and how it is spending it,” he said. “It is a black hole for money.”

A 2016 inspector general report indicated the Pentagon could not account for how it spent $6.5 trillion during the last two decades, Overfelt said.

The $600 billion the Pentagon receives does not include additional funding for classified operations by the CIA and NSA. However, Overfelt said insiders estimate this secret budget pushes military spending over $1 trillion per year — a third of the U.S. budget.

“It is no secret there is always enough money for a bigger military and more jails, but never enough for education and the poor,” he said. “Instead of this money going to health care and education for our citizens who so desperately need it, it goes to padding the pockets of weapons manufacturers on Wall Street.”

Overfelt said most of the military funding does not go to fight wars, but to secure American capital across the world.

“Around the world the State Department supports corrupt governments to ensure our access to their resources,” he said. “We take their resources and bring them into our country, and then we build walls to ensure they cannot come here and participate in the wealth we have taken from them.”

Overfelt offered a three-pronged approach to demilitarization including slashing the military budget and reinvesting in health care and other programs, ending the war on drugs, and stopping the war on immigrants.

“The war on immigrants has nothing to do about crime or safety,” he said, “but is purely about ensuring cheap laborers around the world cannot leave the systems they are trapped in. The money flows across international borders, but the workers can’t follow the money.”

For more information on the Poor People’s Campaign, see its website at www.poorpeoplescampaign.org.