Political rally results in mass destruction

Phillips County Review

Note: The big day is finally upon us — the Kirwin Sesquicentennial will be held this Saturday, Oct. 5, with the parade getting underway at 10 a.m. In recognition of that rare celebration, the Phillips County Review has been running original historical articles on the community.

Kirwin, Kansas, was born in fire. Literally. Founded in 1869, it was not until December 1870 that it was platted and the Kirwin Town Company formed.

Just months later a massive prairie fire swept over the community, destroying most of what little progress had been made in building the frontier settlement.

Rising from the ashes, for the next 20 years Kirwin became the most prominent town in northwest Kansas. During that time fire continued to be Kirwin’s constant nemesis, threatening it through accidents, acts of god, and the malice of man.

While prairie fires regularly swept around the outpost on plains, and accidents with lanterns, chimneys and fireworks caused damage to structures in town on a regular basis, it was the malice of man that caused the most destructive fire in the history of Kirwin, consuming the better part of the east side of the town square in 1888, as well as a portion of the south side.

Violent Political Conflict Explodes In Phillips County

Late that year prairie fires, while dangerous, were the least of Phillips County’s problems as “incendiaries” had been engaging in a campaign of destroying entire business districts in the late 1880s.

The same week as the most recent Kirwin prairie fire swept around Kirwin in October 1888, the main block of the Logan business district was destroyed in a large blaze. Occurring at the tail end of a very heated election season, the Logan outbreak took place the very same day as the Phillips County Union Labor political party convention, chaired by L.F. Fuller of Logan.

At the time it was widely believed to have been “incendiary” in origin, with fingers of accusation being pointed back and forth between Union Laborites, Republicans and Democrats. Incendiary was the term used back then for arson.

This fire came in the midst of considerable political strife taking place throughout Kansas generally and Phillips County in particular. “Kansas Populism,” as it was called, was spreading across the state and was being embraced by farmers, threatening the entrenched political power structure.

The Union Labor Party, an early form of the Populist Party, had been established in the American Midwest in 1887 and was a grassroots partnership of farmers and factory workers challenging both the Democratic Party and the Republican Party for the votes of disaffected blue collar workers politicized by industrial conflicts, low wages, low farm prices, and farm foreclosures.

The Union Labor Party was a successor organization to the National Farmers Alliance and Greenback Party movements of the 1870s and early-1880s. Both had been agrarian organizations whose goals mirrored those of the Farmer’s Grange, and evolved into the Union Labor Party by the late 1880s. After the 1888 election the Union Labor Party itself was absorbed into the broader Populist Party of the 1890s.

Establishing a nationwide platform of increasing grain prices, raising wages and reducing factory employee hours, Union Laborites were attacked by their political opponents as being “anarchists.” Despite this, they were very well organized in Phillips County in 1888, having a large county membership and formal party organizations in 24 out of the county’s 30 townships.

That same year there were at least eight Union Labor-supporting newspapers in the county and the surrounding area, including the Logan Freeman, the Athol People’s Friend, the Kensington Union Labor Trumpet, the Hill City Sun, the Phillipsburg Democrat, the Long Island Inter Ocean, the Almena Plaindealer and the Kirwin Independent.

The Union Labor leadership in Phillips County came from Logan, Kirwin, Marvin (Glade), Big Bend (Speed), Stuttgart, and Agra with the significant membership lists including surnames which would sound familiar to 21st-century residents.

And their county convention had just been held in Phillipsburg on October 10, 1888, with Logan burning that night.

This convention seemed to agitate the volatile local political situation in the lead up to the Logan fire, and the even larger one that was about to hit Kirwin.

Almost sensing a problem was heading towards Kirwin in the immediate aftermath of the Logan fire, the Kirwin Chief used the controversy to chime in regarding that town’s own vulnerability to fire–

“This was about the best business block in Logan, and will be a great loss to the town. We might say here that this is another reminder that Kirwin has no protection against fire.”

In the same issue of the newspaper and for the first time in all of its many months of pleas urging the creation of a fire defense infrastructure, the Chief even went so far as to urge its readers to buy fire insurance.

Matters finally came to a head when a major Union Labor rally was planned to be held at the Kirwin Opera House on Saturday, October 27, 1888, with the keynote speaker being Populist firebrand Sarah E.V. Emery, author of “Seven Financial Conspiracies.”

Republican politician–turned Greenbacker–turned Populist U.S. Congressman John Davis, Junction City, said of Emery’s publication, “In the year 1888, 50,000 copies of Mrs. Emery’s little book were showered among the people of Kansas. Under their fructifying influence the seeds of thought began to spring up in every heart. The rage of the enemy knew no bounds. Great lawyers and judges of courts wrote pamphlets and newspaper broadsides which were circulated by Republican committees and corporation newspapers as campaign documents. Smaller men called the little book ‘The Union Labor Bible.’ They cursed it in their speeches, tore it to pieces in the presence of their audiences, dashed it to the floor, spat upon it, trampled it under foot. All this but proved the rage of the lion that had been wounded, the pain of the whale that was pierced, or the bird that was hit.”

After the announcement of the Kirwin Union Labor rally was made there was a major pushback from opposing political forces. With Kirwin community leaders receiving at least two letters threatening the town’s destruction should it follow through on its plans, the event moved forward as scheduled.

On the appointed afternoon the rally got underway in the midst of a huge crowd. With Emery taking to the podium, the Kirwin Chief reported, “the Kirwin Opera House was packed to its utmost capacity. Mrs. Emery spoke for about one hour and a half, during which she spoke of the farmers being in debt. That their farms were mortgaged for all they were worth, that the people were reduced to poverty and that it had been brought about by class legislation.”

The Chief continued, “She attempted to show that leaders had entered into a conspiracy with the shylocks of Wall Street to allow the monopolists to obtain control of the finances of the country.”

With Emery blaming the Republican Party for this state of affairs, after she finished the G.O.P had a rebuttal speaker, Philip P. Campbell, Pittsburg, address the capacity crowd. At the time Campbell was a lawyer, but a decade later would be elected as Kansas’ Third District Representative to the United States Congress and serve in that role for two decades.

According to the Chief, “Mr. Campbell made a forcible though impromptu speech, and handled the unproven assertions and wild theories of his opponent in a merciless manner. He gave his hearers some logical facts about the relations of labor and capital; about the causes of hard times. He said that class legislation was not responsible for a failure of crops, and that it was impossible for farmers to flourish when the country was suffering from an almost total failure of crops. He then devoted some time to the wild theories in the little book of which Mrs. Emery was the inspired author.”

As the town was still on edge from the afternoon’s excitement, that night the Union Laborites gathered for a second rally, with a lead-off speech by the party’s county chair, L.F. Fuller, Logan. Fuller had just arrived in Kirwin after having spent the day in Kensington, where another large Union Labor rally/Republican counter-rally had also been held.

With Emery following Fuller, also addressing this evening Kirwin rally was 39-year-old attorney and editor of the Kirwin Independent, Clayton “C.J.” Lamb. Lamb was one of seven men on the Phillips County Union Labor Central Committee, as well as one of six men on the State of Kansas Union Labor Central Committee.

While Lamb was in the midst of his speech, he was suddenly yanked from the podium, arrested, and taken to Phillipsburg in custody.

As the day’s controversies were echoing up and down the streets of Kirwin, Emery checked into the Commercial Hotel on East Main Street.

Then, just mere hours later, fire broke out in four different places on the east and south sides of the Kirwin Square. One of those primary points of ignition was in the back offices of C.J. Lamb’sKirwin Independent.

The Alarm is Sounded

The alarm for the Kirwin conflagration was sounded not long after midnight, Sunday morning, Oct. 28, 1888, with flames appearing simultaneously on the east and south sides of the square.

On the east side the block was anchored on its north by the brick First National Bank building (also known as the Kirwin State Bank) and on the far south by the home of R.I. Palmer, an owner of the Kirwin Chief. In between the bank and Palmer’s house were wall-to-wall adjoining wood frame buildings. Tinderboxes.

The fire on this side of the square was started in three places — at the rear of the Kirwin Independent newspaper, in Bradley’s Lumber Yard and in Noble’s Livery Stable, just north of Palmer’s home.

A fourth site on the south side of the square was also targeted by the incendiaries. This smaller block was anchored by C.C. Stone’s Clothing Store on its east, and Ingersoll’s, the largest mercantile store in Phillips County, on the west. In between was Streble’s building and a store owned by August Stockmann.

The fire on this side was started behind Stone’s place.

Kirwin had two newspapers at the time — the Chief, and the Independent. By morning it would have just one, with the Independent ceasing to exist.

The Great Fire Rages

A report in the Phillipsburg Democrat told the tale–

“The people of Kirwin were startled last Sunday morning about 1 o’clock, by hearing the cry, fire! The fire was seen to break out in four different places. It broke out on the south side of the square just behind Stone’s store. On the east side it broke out in Bradley & Co.’s lumber yard, and just behind C.J. Lamb’s printing office, and Noble’s livery barn. It is reported that a letter was written to a gentleman in Kirwin stating that Kirwin was doomed.”

According to the reporting of the Chief—

“Early last Sunday morning one of the most destructive fires in the history of the city occurred. The alarm of fire was given and our drowsy citizens on going to their doors and windows were horror-stricken to find the entire southeast corner of the square was already in flames.

“It was only a few minutes before hundreds of willing hands were ready to do anything which was possible to check the flames, but with no available means of fighting the fire little could be done.

“The stores were opened as soon as it was found impossible to save them and goods were carried out into the street a safe distance from the fire and thus the damage was made as light as possible.

“Men, women and children worked like superhuman beings, some men doing more work in thirty minutes than they had done before in a whole year.

“The fire was evidently the work of incendiaries, though no positive clue has yet been obtained as to the parties who did the work.

“From the fact the fire was set in different places at the same time, there is no possibility of its being accidental.

“Several theories have been advanced and we hope in a short time the truth will have been ascertained.”

The Chief report continued, “A number of parties burnt out will erect brick buildings in the spring if they do not before.

“The noble ladies of Kirwin cannot be too highly commended for their bravery and noble work in saving property. Thousands of dollars were saved through their efforts.

“It is said there was less noise made than at any other fire on record. Some men slept within three blocks of the fire and did not know it until morning.”

The Damage

Totally destroyed on the east side were Stone’s Grocery (building owned by August Stockmann), Keckley Bros. Merchandise, George Noble Livery, Osborne & Co. Implement, Bradley Lumber, Bartlett Produce, Kimberly Produce, Camp Produce, the Kirwin Independent newspaper, Walker Furniture (building owned by August Stockmann), Oliver & Boddington Meat & Fur, Wilcox Barber Shop, Stockmann Mercantile, Troup’s Novelty Store, Taylor Notions (building owned by August Stockmann). The First National Bank building was damaged.

On the south side, Ingersoll & Co. was damaged, as was the Streble Building and another store owned by Stockmann. Stone Clothing was totally destroyed.

The Cause

There was ample evidence arson was involved, with the Phillipsburg Dispatch laying out the case that same week in a report stating–

“The cause of the fire will, we presume, always be a mystery, but was undoubtedly set on fire by some malicious persons.

“The fire was discovered in the Charles Hull building occupied by C.C. Stone, and in a few seconds, even before the fire had broken through this building, the second fire was discovered in or near the rear of C.J. Lamb’s printing office, and before these could have thrown out any sparks or sufficient heat to cause fire in other places, it was discovered that the inside of the livery barn, south of those already mentioned, was on fire.

Both the Dispatch and Democrat reported threatening letters being received prior to the blaze, with the Dispatch providing the most details–.

“It is reported Dr. R.H. Trusdle had received a letter before this fire occurred stating there was a move on foot to burn Phillipsburg and Kirwin. But he had failed to inform the city authorities as to this matter.

“If this letter had been made public the people would have doubtless been on the alert.”

In a special report just two days after the blaze the Topeka Daily Capital said–

“It is evident the fire was the work of incendiaries, but there is as yet no clue as to the perpetrator or perpetrators of the dastardly deed.

“One young lady, Miss Lizzie Bannister, the operator in the Central Telephone office, covered herself with glory by starting to mount a ladder with a pail of water to pour on the flames which were menacing the First National Bank. She was restrained from making the perilous ascent only by the interference of several gentlemen who held her back.

“A number of the parties will rebuild in a short time. Several of them will erect brick buildings.”

Who Set The Fire…And Why?

With different political factions accusing one another of starting the inferno, the only thing which was certain was that a major part of the economic base of the Kirwin community was destroyed.

The arrest of C.J. Lamb, and both the timing of the fire on the night of the rally and the fact one ignition site of the fire was in Lamb’s offices were all major issues of discussion.

Even the arrest prominently pitted one political party against the other. Kirwin’s C.J. Lamb was a noted Union Laborite, an attorney, and the publisher of the Kirwin Independent. The warrant under which Lamb had been taken into custody in the midst of making his speech had been issued against him by Lamb’s polar opposite — Phillipsburg’s George W. Stinson, a noted Republican, an attorney and former publisher of the Phillipsburg Herald.

The two men had been in conflict for some time, with it reaching a breaking point after Lamb reprinted a September 6, 1888 story from the Logan Republican reporting on Stinson being the father of an unborn child of Blanche Ford, the cousin of Stinson’s recently deceased wife.

The Republican article stated Stinson, upon finding out Ford was with child, left for parts unknown, resulting in Ford attempting suicide.

Stinson had a criminal libel warrant issued against Lamb for running the article (Stinson took no action against the Republican), with that warrant being held and then finally served two months later as Lamb was making his speech at the Union Labor rally in Kirwin.

However within a short time after the Kirwin conflagration Lamb turned the tables, as Stinson himself was arrested for bastardy, with the charges against Lamb being dismissed.

Miss Ford, being unmarried and pregnant, was afterward incarcerated and held as an inmate at the Phillips County Poor Farm.

This was all but a sideshow to the identification of the incendiaries setting Kirwin ablaze, with the finger-pointing first placing blame on Stinson for the mass destruction of a major part of the Kirwin business district.

As more information came to light the conflict between the Union Labor Party and the Republican Party was blamed and took center stage as being the real cause. And, as with any good political conflict, each side began blaming the other.

On November 1 the Cawker City Public Record reported on the carnage in Kirwin, noting “the fire is supposed to have been instigated by the anarchistic element which predominates in Phillips County.”

On November 1 the Phillipsburg Dispatch wrote–

“There are various rumors as to the cause of this fire; many think it the plot of an element of anarchy, now in private organization. Our citizens should be well guarded against these out-laws. A Kirwin gentleman was heard to say the day after the fire that if a Union Labor rally was held in Phillipsburg the city should put on twenty night watchmen or have the town burned.”

Also on November 1 the Logan Freeman, after first pointing out Lamb’s controversial Union Labor newspaper story on Stinson originated in a Republican newspaper, wrote–

“The arrest of Lamb for a libel committed in September and his arrest followed by the burning of his office together with 12 other buildings in Kirwin while he was absent, are coincidence that will bear study upon the part of thinking men all over the country. Look carefully at the ones who shout anarchy and you will see a true anarchist, or his pliant tool.”

In a separate article in that same issue, the Freeman observed–

“Next followed the arrest of C.J. Lamb, editor of the Union Labor paper. Lamb was taken to Phillipsburg and while away from home his office and everything in it, on which there was not one cent of insurance, was burned.

“This fire occurred on the night of Mrs. Emery’s meeting in Kirwin — breaking out at the same hour in the night as the Logan fire and in several places at once. The same identical howl about Union Labor men setting the fire was raised by the same class of men that raised the howl in Logan, and have been howling ‘anarchy’ for months past. What are they trying to cover up?

“Before the fire a leading Republican of Kirwin remarked to a man who was collecting a fund to pay expenses of the meeting to be held, asking if he was taking up a collection to buy rope to hang C.J. Lamb and others like him.

“They have no ground for talking as they do unless it is for the purpose of throwing suspicion on innocent parties in order to cover up their dirty work.

“Will the people aid these excrescences upon society to carry out their infernal schemes on election day?”

On November 2 the Cawker City Times referred to the debate going on regarding the Kirwin incendiary’s identity and motive, writing “It was supposed to be the work of political spite.”

Also on November 2, from the Winfield Weekly Visitor—

“The office of the Kirwin Independent, a Union Labor paper, was burned last week. It was the work of an incendiary.”

By November 9, almost two weeks after the fire, the Kansas City Gazette noted–

“The recent fire at Kirwin is now laid to Union Labor miscreants.”

More details became available on November 14, as the Concordia Kansas Kritic explored the “political spite” motive–

“And now worse than any comes the news from Kirwin. Mrs. Emery was billed to speak there. Prominent Republicans said she should not speak there, and if she did speak the town would suffer in consequence.

“She did speak, and in the midst of the meeting, the editor of the Kirwin Independent, C.J. Lamb, chairman of the Union Labor Congressional Committee, was arrested on an old trumped up charge of libel.

“He was taken to Phillipsburg, the county seat from where he did not get back until Sunday morning.

“During the night a fire broke out in different places and property was destroyed to the amount of $50,000.

“One of the places the fire was first discovered was in Mr. Lamb’s printing office which was then completely enveloped in flames.

“The fire is conceded by all to be the work of incendiaries. The cry of ‘anarchy’ was at once raised and an attempt made to fasten the crime on to the Union Labor men, until it was discovered that on Mr. Lamb’s property there was not one dollar of insurance, while a Republican, whose loss was about $5,000 carried insurance.

“Could circumstantial evidence be more conclusive? Not only will they resort to falsehood and the vilest slander but they will use dynamite and fire to defame the character of the men whose arguments they can not answer.”

The Kirwin Independent remained closed for a full year, before reopening under a new owner who espoused independent politics. Afterwards evolving the newspaper’s slant towards Republican, in 1902 it changed its name to the Kirwin Kansan, continuing operations until its October 1, 1942 issue — it’s Kirwin Old Settlers Day issue.

“This announcement comes at a time when many old timers plan to gather in Kirwin on Tuesday, October 6, 1942 to recall the past history of this splendid community,” the newspaper wrote. “We have made arrangements with the Phillips County Review to fulfill our subscription obligations. You will receive this splendid county paper for whatever period you have paid your subscription in advance.”

Within weeks of the big fire Clayton J. Lamb moved to Lawrence, Kansas, serving for a time as the associate editor of the Jeffersonian Gazette. Eventually ending up back in the state of his birth, Michigan, Lamb ran unsuccessfully as a Social Democrat for lieutenant governor there in 1900 and for governor in 1904. Lamb passed away in Glendale, California, in 1908.

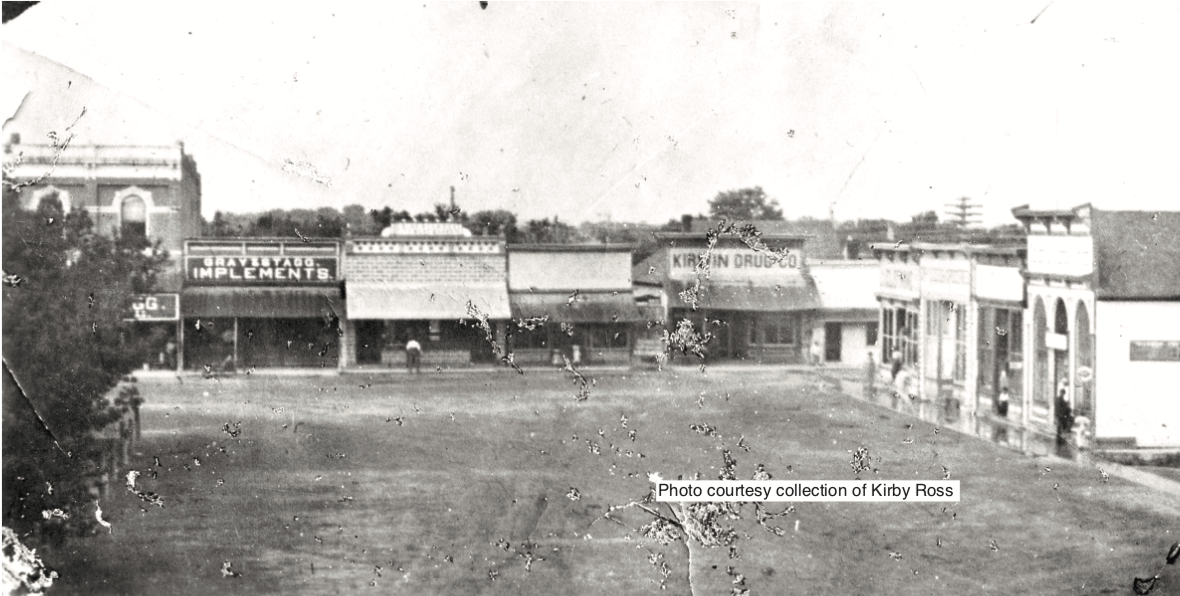

Rebuilding — Again

Just as the town had done after the prairie fire swept over it in 1871, Kirwin immediately began rebuilding.

With most of the contents of the buildings having been saved by the townspeople during the 1888 destruction, within 72 hours of the fire most businesses had set up their operations at other points around the square.

Keckley Bros. Merchandise moved into the Traders Bank on the northeast part of the square — but not for long. Keckley’s store, being made of stone, was quickly repaired and reopened in the burnt district two weeks after the fire.

Oliver & Boddington Meat Market and Fur Buyers set up shop on the bandstand in the center of the town square, and within a week was boldly announced its continuing existence by advertising, “Oliver & Boddington will pay more for hides than any other shop in Phillips County.”

In short order they were moving into a store on the southwest side and proceeding as before.

While he rebuilt, August Stockmann moved into a Streble building near other properties he owned on East Main Street, before moving into the Downs Hardware & Implement building on the west side of the square.

Within a year Stockmann had constructed a new store, bigger and better than ever, putting up a grand seamless brick extension to the bank building back on the east side that would define Kirwin for over a century to come.

Walker Furniture moved into the Styles Building in the northwest square and made the best out of a bad situation — they held a fire sale, literally, just days after the conflagration.

Walker Furniture moved into the Styles Building in the northwest square and made the best out of a bad situation — they held a fire sale, literally, just days after the conflagration.

“I am offering some furniture which was slightly damaged in the fire at Great Bargains,” Walker’s advertising said.

Troup’s moved into Barnard’s on the northeast square, with their sale ads shouting “Fire! Fire!! Great reduction in prices since the fire at the Troup Novelty Store.”

C.E. Bradley of Bradley Lumber, in a tight financial bind, sent out a plea asking his customers to whom he had extended credit to come to his aid.

“Having sustained a severe loss in the fire, I desire to say to the parties who are owing me that I need the money badly to start in business again and shall regard it as a great favor if you will call and settle at once. I expect to at once open up a lumber and coal yard in Kirwin and need what you owe me in order to do so.”

Ever the entrepreneur and seeing a business opportunity, three days after the disaster Kirwin insurance salesman and real estate agent W.J. Palmer was pressing other businesses in town to come to him and get their buildings insured against fire.

And eleven days after the Great Fire of Kirwin the Kirwin Chief was observing, “The Streble building which was badly damaged by the fire has been repaired this week.”

Led by Stockmann and his iconic new mercantile building, the entire east side was rebuilt with striking designs in either stone or brick. While one of those “new” buildings would burn in the 1950s, because of the materials used this time the fire didn’t spread and destroy the entire block.

The rest of those early buildings stood for many decades before every one of them, except for one minor structure, succumbed to old age.

They finally fell not because of fire, but because of time.

————————–