These priests, deacons, monks and lay people now teach middle-school math. They counsel survivors of sexual assault. They work as nurses and volunteer at nonprofits aimed at helping at-risk kids. They live next to playgrounds and day care centers. They foster and care for children.

And in their time since leaving the church, dozens have committed crimes, including sexual assault and possessing child pornography, the AP’s analysis found.

A recent push by Roman Catholic dioceses across the U.S. to publish the names of those it considers to be credibly accused has opened a window into the daunting problem of how to monitor and track priests who often were never criminally charged and, in many cases, were removed from or left the church to live as private citizens.

Each diocese determines its own standard to deem a priest credibly accused, with the allegations ranging from inappropriate conversations and unwanted hugging to forced sodomy and rape.

Dioceses and religious orders so far have shared the names of more than 5,100 clergy members, with more than three-quarters of the names released just in the last year. The AP researched the nearly 2,000 who remain alive to determine where they have lived and worked _ the largest-scale review to date of what happened to priests named as possible sexual abusers.

In addition to the almost 1,700 that the AP was able to identify as largely unsupervised, there were 76 people who could not be located. The remaining clergy members were found to be under some kind of supervision, with some in prison or overseen by church programs.

The review found hundreds of priests held positions of trust, many with access to children. More than 160 continued working or volunteering in churches, including dozens in Catholic dioceses overseas and some in other denominations. Roughly 190 obtained professional licenses to work in education, medicine, social work and counseling _ including 76 who, as of August, still had valid credentials in those fields.

The research also turned up cases where the priests were once again able to prey on victims.

After Roger Sinclair was removed by the Diocese of Greensburg in Pennsylvania in 2002 for allegedly abusing a teenage boy decades earlier, he ended up in Oregon. In 2017, he was arrested for repeatedly molesting a young developmentally disabled man and is now imprisoned for a crime that the lead investigator in the Oregon case says should have never been allowed to happen.

Like Sinclair, the majority of people listed as credibly accused were never criminally prosecuted for the abuse alleged when they were part of the church. That lack of criminal history has revealed a sizable gray area that state licensing boards and background check services are not designed to handle as former priests seek new employment, apply to be foster parents and live in communities unaware of their presence and their pasts.

It also has left dioceses struggling with how _ or if _ former employees should be tracked and monitored. Victims’ advocates have pushed for more oversight, but church officials say what’s being requested extends beyond what they legally can do. And civil authorities like police departments or prosecutors say their purview is limited to people convicted of crimes.

That means the heavy lift of tracking former priests has fallen to citizen watchdogs and victims, whose complaints have fueled suspensions, removals and firings. But even then, loopholes in state laws allow many former clergy to keep their new jobs even when the history of allegations becomes public.

“Defrocked or not, we’ve long argued that bishops can’t recruit, hire, ordain, supervise, shield, transfer and protect predator priests, then suddenly oust them and claim to be powerless over their whereabouts and activities,” said David Clohessy, the former executive director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, who now heads the group’s St. Louis chapter.

“IT WAS SUPPOSED TO MAKE ABUSE HISTORY”

When the first big wave of the clergy abuse scandal hit Roman Catholic dioceses in the early 2000s, the U.S. bishops created the Dallas Charter, a baseline for sexual abuse reporting, training and other procedures to prevent child abuse. A handful of canon lawyers and experts at the time said every diocese should be transparent, name priests that had been accused of abuse and, in many cases, get rid of them.

Most dioceses decided against naming priests, however. And with the dioceses that did release lists in the next few years_ some by choice, others due to lawsuit settlements or bankruptcy proceedings _ abuse survivors complained about underreporting of priests, along with the omission of religious brothers they believed should be on those lists.

“The Dallas Charter was supposed to fix everything. It was supposed to make the abuse scandal history. But that didn’t happen,” said the Rev. Thomas Doyle, a canon lawyer who had tried to warn the bishops that abuse was widespread and that they should clean house.

After the charter was established in 2002, some critics say dioceses were more likely to simply defrock priests and return them to private citizenship.

Before 2018’s landmark Pennsylvania grand jury report, which named more than 300 predator priests accused of abusing more than 1,000 children in six dioceses, the official lists of credibly accused priests added up to fewer than 1,500 names nationwide. Now, within the span of a little more than a year, more than 100 dioceses and religious orders have come forward with thousands of names _ but often little other information that can be used to alert the public.

Some of the lists merely provide names, without details of the abuse allegations that led to their inclusion, the dates of the priests’ assignments or the parishes where they served. And many don’t disclose the priests’ status with the church, which can vary from being moved into full retirement to being banished from performing public sacraments while continuing to perform administrative work. Only a handful of the lists include the last-known cities the priests lived in.

Over nine months, AP reporters and researchers scoured public databases, court records, property records, social media and other sources to locate the ousted clergy members.

That effort unearthed hundreds of these priests who, largely unwatched by church and civil authorities, chose careers that put them in new positions of trust and authority, including jobs in which they dealt with children and survivors of sexual abuse.

At least two worked as juvenile detention officers, in Washington and Arizona, and several others migrated to government roles like victims’ advocate or public health planner. Others landed jobs at places like Disney World, community centers or family shelters for domestic abuse. And one former priest started a nonprofit that sends people to volunteer in orphanages and other places in developing nations.

The AP determined that a handful adopted or fostered children, sponsored teens and young adults coming to the U.S. for educational opportunities, or worked with organizations that are part of the foster care system, though that number could be much higher since no public database tracks adoptive or foster parents.

Until February, former priest Steven Gerard Stencil worked at a Phoenix company that places severely disabled children in foster homes and trains foster parents to care for them. Colleagues knew he was a former priest, but were unaware of past allegations against him, according to Lauree Copenhaver, the firm’s executive director.

Stencil, now 67, was suspended from ministry in 2001 after a trip to Mexico that violated a diocese policy forbidding clerics from being with minors overnight. Around that time, a 17-year-old boy also complained that Stencil, then pastor of St. Anthony Parish in Casa Grande, Ariz., had grabbed his crotch in 1999 in a swimming pool. The diocese determined it was accidental touching, but turned the allegations over to police. No criminal charges were filed.

Since 2003, Stencil’s name has appeared on the Tucson diocese’s list of clerics credibly accused of sexually abusing children, and his request to be voluntarily defrocked was granted in 2011.

Copenhaver said Stencil passed a fingerprint test showing he did not have a criminal history when he was first hired part time by Human Services Consultants LLC 12 years ago.

“We did not have any knowledge of his indiscretions, and had we known his history we would not have hired him,” she said, emphasizing that he did not have direct access to children in his job.

Stencil was fired from the company for unrelated reasons earlier this year. He later said in a post on his Facebook page that he was working as a driver for a private Phoenix bus company that specializes in educational tours for school groups and scout troops.

“I have always been upfront with my employers about my past as a priest,” Stencil wrote in an email to the AP when asked for comment. He said he unsuccessfully asked years ago for his name to be removed from the diocese’s list, adding, “Since then, I have decided to simply live my life as best I can.”

The AP’s analysis also found that more than 160 of the priests remained in the comfortable position of continuing to work or volunteer in a church, with three-quarters of those continuing to serve in some capacity in the Roman Catholic Church. Others moved on as ministers and priests in different denominations, with new roles such as organist or even as priests in Catholic churches not affiliated with the Vatican, sometimes despite known or published credible accusations against them.

In more than 30 cases, priests accused of sexual abuse in the U.S. simply moved overseas, where they worked as Roman Catholic priests in good standing in countries including Peru, Mexico, the Philippines, Ireland and Colombia. The AP found that in all, roughly 110 clergy members moved or were suspected of moving out of the U.S. after allegations were made.

At least five priests were excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church because of their refusal to stop participating in other religious activity.

More than three decades ago, James A. Funke and a fellow teacher at a St. Louis Catholic high school, Jerome Robben, went to prison for sexually abusing male students together. Funke, released in 1995, was eventually bounced from the priesthood. But years later, the two men joined together again, promoting Robben as the leader of a church of his own making.

Since 2004, Missouri records show that Robben has listed his St. Louis home as the base for a religious organization operating under at least three different names. Beginning in 2014, those papers have identified Funke as the order’s secretary and one of its three directors.

Mary Kruger, whose son committed suicide when he was 21 after being abused by the men in high school, said she raised fresh concerns about Robben in 2007 when she heard he was presenting himself as a cleric.

At the time, he was being considered for promotion to bishop in a conservative Christian order based in Ontario, Canada. Kruger said members of the order told her that Robben had dismissed questions about his abuse conviction, claiming he had merely rented an apartment to Funke and that police blamed him for not knowing what went on inside.

Robben eventually was defrocked from the Christian order, and apparently then started his own. Until last year, when its paperwork expired, the group was registered with Missouri officials as the Syrian Orthodox Exarchate. However, a Facebook post from 2017 identified Robben _ photographed wearing a crown and gold vestments _ as the leader of a Russian Byzantine order raising money to build a monastery in Nevada.

Funke refused comment when approached by an AP reporter, and Robben did not respond to requests for comment.

“If they could wind up in jail next week, I’d be ecstatic,” Kruger said. “I think as long as they’re alive, they’re dangerous.”

LEFT THE CHURCH, COMMITTED CRIMINAL OFFENSES

As early as 1981, church officials knew of allegations that Roger Sinclair had acted inappropriately with adolescent boys. Two mothers at St. Mary’s Parish in Kittanning, Penn., wrote a letter to the then-bishop saying that Sinclair had molested their sons, both about 14 at the time.

Sinclair played a game where he would shake hands and then try to shove his hand at their genitals, the mothers said in their letter, parts of which were made public last year as part of the landmark report in Pennsylvania. They said he also tried to put his hands down one of the boy’s pants.

Other accusations emerged about Sinclair showing dirty movies to boys in the rectory, exposing himself and possibly molesting a teen he had taken on a trip to Florida a few years earlier. After a group of mothers called the police for advice, the police chief told them he had heard the rumors but took no action, according to documents reviewed by the Pennsylvania grand jury.

The church sent Sinclair for treatment, returned him to ministry and provided him with a letter that listed him as a priest in good standing so he could be a chaplain in the Archdiocese of Military Services, according to the grand jury. That assignment took him to at least four different states, including Kansas, where in the early ‘90s he was a chaplain at the Topeka State Hospital, a now-closed state mental hospital that had a wing for teenagers.

He was fired from that assignment in 1991 after trying multiple times to check out male teenage patients to go see a movie. Administrators said he had managed “to gain access to a locked unit deceitfully.”

Sinclair was removed from ministry in 2002 while the diocese investigated claims from a victim who said the priest sexually abused him in the rectory and on field trips beginning at Sinclair’s first assignment as a priest. He resigned a few years later, before the church concluded proceedings to defrock him.

When he started serving on the board of directors of an Oregon senior center and working as a volunteer there, he was required to pass a background check because the center received federal dollars for the Meals on Wheels program. But no flags were raised because he was never charged in Pennsylvania.

According to accounts from both former center staffers and law enforcement officials, Sinclair’s downfall began when the center’s then-director looked outside and saw him with his hand down the young man’s pants. He immediately barred Sinclair from the center, but left it up to the man’s family to decide whether to press charges. Three months later, after learning why Sinclair had been absent, an employee went to the police out of fear the former priest would target someone else.

Now-Sgt. Steven Binstock, the lead investigator in Oregon, said Sinclair immediately confessed to committing multiple sexual acts with the developmentally disabled man. He also confessed to sexual contact with minors in Pennsylvania 30 years earlier.

“He was very vague, but he did tell us that it was some of the same type of behaviors, the same type of incidents, that had occurred with the victim that happened here,” Binstock told the AP.

The Pennsylvania diocese had never warned Oregon authorities about Sinclair because it stopped tracking him after he left the church. The diocese, which did not tell the public Sinclair had been accused of abuse until it released its list in August 2018, declined to comment on his case.

The AP’s analysis of the credibly accused church employees who remain alive found that more than 310 of the 2,000 have been charged with crimes for actions that took place when they were priests. Beyond that, the AP confirmed that Sinclair and 64 others have been charged with crimes committed after leaving the church, with most of them convicted for those crimes.

Some of the crimes involved drunken driving, theft or drug offenses. But 42 of the men were accused of crimes that were sexual in nature or violent, including a dozen charged with sexually assaulting minors. Thirteen were charged with distributing, making or possessing child pornography, and several others were caught masturbating in public or exposing themselves to people on planes or in shopping malls.

Five failed to register in their new communities as sex offenders as required due to their sex crime convictions.

Priests and other church employees being listed on sex offender registries at all is a rarity _ the AP analysis found that only 85 of the 2,000 are. That’s because church officials often successfully lobbied civil authorities to downgrade charges in exchange for guilty pleas ahead of trials. Convictions were sometimes expunged if offenders completed probationary programs or the charges were reduced below the level required by states for registration.

Since sex offender registries in their current searchable form didn’t begin until the 1990s, dozens also were not tracked or monitored, because their original sentences already had been served before the registries were established.

The AP also found that more than 500 of the credibly accused former priests live within 2,000 feet of schools, playgrounds, childcare centers or other facilities that serve children, with many living much closer. In the states that restrict how close registered sex offenders can live to those facilities, limits range from 500 to 2,000 feet.

Decades after Louis Ladenburger was temporarily removed from the priesthood to be treated for “inappropriate professional behavior and relationships,” he was hired as a counselor at a school for troubled boys in Idaho.

Ladenburger was arrested in 2007 and accused of sexual battery; in a deal with prosecutors, he pleaded guilty to aggravated assault. He served about five months in prison.

According to Bonner County, Idaho, sheriff’s reports, students said Ladenburger told them he was a sex addict. During counseling sessions, they said, the former Franciscan priest rubbed their upper thighs and stomachs, held their hands and gave them shoulder and neck massages. If students expressed confusion about their sexual identities, the sheriff’s reports say he fondled them and performed oral sex on them.

Ladenburger was fired from the school. In an interview with sheriff’s officials at the time, he “admitted being a touchy person,” kissing many students and having his “needs met by the physical contact” with the boys.

By then, he’d been gone from the church for more than a decade _ in 1996, the Vatican had granted his request to be released from his vows. No officials from his religious order or from the dioceses in six different states where he had served had warned the school or provided details of the allegations against him when he was a priest.

In a lawsuit involving a sexual abuse allegation against another member of the Franciscan order, the complaint cited Ladenburger as an example of the harm done when church officials don’t report accusations of abuse to law enforcement, saying he likely never would have been hired at the school if the Franciscans had reported him when they first became aware.

“For all intents and purposes, they set loose a ticking time bomb that exploded in 2007,” the lawsuit said.

WHY FORMER PRIESTS AREN’T TRACKED

If priests choose to leave their dioceses or religious orders _ or if the church decides to permanently defrock them in a process known as laicization _ leaders say the church no longer has authority to monitor where they go.

After the Dallas Charter came a rush to laicize, resulting in more than 220 of the priests researched by the AP being laicized between 2004 and 2010. Roughly 40% of all the living credibly accused clergy members had either been laicized or had voluntarily left the church.

The laicized priests also are increasingly younger, giving them even more years to lead unsupervised lives, according to Deacon Bernie Nojadera, the executive director of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Secretariat of Child and Youth Protection.

“That does create an opportunity for them to seek a second career,” Nojadera said. “So this is something a number of dioceses are grappling with and trying to figure out.”

For priests who don’t leave the church, dioceses and religious orders have more options to impose restrictions and monitoring. But how and whether that’s done ranges widely from diocese to diocese, since the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops cannot mandate specific regulations or procedures.

The AP found that the dioceses that released lists more than a decade ago have the most robust of the handful of existing programs.

In Chicago, accused priests who are removed from ministry can opt to join a program started in 2008 in which they continue to receive treatment, benefits and help, and get to “die a priest.” In exchange, they must sign over their right to privacy and agree to obey rules such as not living near a school.

“The monitoring is intrusive … I track their phone usage, I require daily logs of where they go, I track their internet usage and check their financial information and records. They have to tell me where they are going to be, who they will be with. And they have to meet with me twice a month face-to-face,” said Moira Reilly, the case manager in charge of the Chicago Archdiocese’s prayer and penance program.

Reilly, a licensed social worker, said many Catholics don’t understand why the church runs the program, instead pushing for every priest accused of abuse to be defrocked.

“If we laicize them or if we let them walk away … no one is watching them,” she said. “I do this job because I truly believe that I am protecting the community. I truly believe that I am protecting children.”

In 2006, the Archdiocese of Detroit hired a former parole officer to monitor priests permanently removed from ministry after credible abuse allegations. Spokesman Ned McGrath said the program requires monthly written reports from the priests that include any contact or planned contact with minors and information on whether they attended treatment among other things.

In other dioceses, priests are sent to retirement homes for clergy or church properties that are easy to monitor, but also are often in close proximity or even share space with schools or universities.

The analysis found that many of the accused clergy members still receive pensions or health insurance from the church, since pensions are governed by federal statute and other benefits are dictated by the bishops in each diocese.

Victims’ advocates and others have suggested dioceses devise a system in which those benefits are contingent upon defrocked priests self-reporting their current addresses and employment.

“All a bishop has to do is tell a predator: ‘Here’s your choice. You’ll go live where I tell you, and you’ll get your pension, health insurance, etc. and be around your brothers but be supervised,’” SNAP’s Clohessy suggested, adding that if the former priests don’t agree, their benefits could be withheld.

But several church officials and lawyers note that robust federal laws prohibit withholding or threatening pensions.

Other experts who study child abuse have suggested the church create a database similar to the national sex offender registry that would allow the public and employers to identify credibly accused priests. But even that measure would not guarantee that licensing boards or employers flag a priest credibly accused but not convicted of abuse.

Doyle, the canon lawyer, said the bishops might not believe they can monitor defrocked priests, but that they could be forthcoming about allegations when potential employers call and could also be required to call child protective services in the states where laicized priests move.

The bishops also could address the issue of oversight by initiating a new framework along the lines of the groundbreaking Dallas Charter, which was approved by the pope, Doyle said. But he added that he didn’t trust the current church leadership to meaningfully address the issue.

“The bishops will never admit this, but when they do cut them loose, they believe they are no longer a liability,” he said, referring to the defrocked priests. “I severely doubt there is an incentive for them to want to fix this problem.”

Nojadera noted that it isn’t that simple, since decisions default to the individual bishops in each diocese.

“We have 197 different ways that the Dallas Charter is being implemented. It’s a road map, a bare minimum,” he said. “We do talk about situations where these men are being laicized and what happens to them. And our canon lawyers are quick to say there is no purview to monitor them.”

LICENSED TO TEACH AND COUNSEL

In many cases, the priests tracked by the AP went on to work in positions of trust in fields allowing close access to children and other vulnerable individuals _ all with the approval of state credentialing boards, which often were powerless to deny them or unaware of the allegations until the dioceses’ lists were released.

The review found that 190 of the former clergy members gained licenses to work as educators, counselors, social workers or medical personnel, which can be easy places to land for priests already trained in counseling parishioners or working with youth groups.

One is Thomas Meiring who, after asking to leave the priesthood in 1983, began working as a licensed clinical counselor in Ohio, specializing in therapy for teens and adults with sexual orientation and gender identity issues.

Meiring maintained his state-issued license even after the diocese in Toledo settled a lawsuit in 2008 filed by a man who said he was 15 when Meiring sexually abused him in a church rectory in the late 1960s.

It wasn’t until 2016 that the Toledo diocese’s request to defrock Meiring was granted. State records show that Ohio’s Counselor, Social Worker and Marriage & Family Therapist Board has never taken disciplinary action against the 81-year-old, who is among several treatment providers listed by a municipal court in suburban Toledo.

“We made noise about him years ago and nobody did anything. It’s mind-blowing,” said Claudia Vercellotti, who heads Toledo’s chapter of SNAP.

But Brian Carnahan, the licensing board’s executive director, said the law grants the authority to act only when allegations have resulted in a criminal conviction.

Multiple calls to Meiring at his home and office were not returned.

Few state licensing boards for professions like counselors or teachers have mechanisms in their background check procedures that would catch allegations that were never prosecuted. Some standard checks are conducted in every state, but the statutes regulating what can be taken into consideration when granting or revoking licenses vary. And because the lists of priests with credible allegations against them were so thin until the past year, there was little to cross-check.

Danielle Irving-Johnson, the career services specialist for the American Counseling Association, said criminal background checks are standard when licensing counselors, but that dismissing an application due to an unprosecuted allegation would be unusual.

“There would have to be substantial evidence or some form of documentation to support this accusation,” Irving-Johnson said.

The Alabama Board of Examiners in Psychology was not aware of the allegations against former priest William Finger when he was licensed as a counselor in 2012. The Brooklyn diocese publicly named Finger only in 2017, even though he had been laicized since 2002 because of abuse allegations.

According to a complaint filed in January with the board, a woman who asked not to be named contacted Finger’s employer last year to say he had abused her for a decade, beginning when he was a priest and she was 12 years old. She said he kissed her, fondled her and digitally penetrated her and also alleged he had sexually abused her sister and a female cousin.

The employer fired Finger, now 83, and reported the allegations to the state’s licensing board.

In many states, allegations dating from before someone was licensed or that never made it to court would have been dismissed. But Alabama’s board issued an emergency suspension because it is allowed to consider issues of “moral character” from any point in a licensed individual’s life.

The decision whether to permanently suspend Finger’s license is pending. He did not return multiple messages from the AP but denied the allegations in a statement to the licensing board. He also remains licensed as a counselor and hypnotherapist in Florida.

The AP also found that 91 of the clergy members had been licensed to work in schools as teachers, principals, aides and school counselors, only 19 of whom had their licenses suspended or revoked. Twenty-eight still are actively licensed or hold lifetime certifications.

That’s almost surely an undercount, since some private, religious or online schools don’t require teachers to be licensed and states like New Jersey and Massachusetts don’t have public databases of teacher licenses.

School administrators in Cinnaminson, New Jersey, knew for years that sixth-grade teacher Joseph Michael DeShan had been forced from the priesthood for impregnating a teen parishioner. But nearly two decades later, he remained in a classroom.

DeShan, now 60, left the Bridgeport, Connecticut, diocese in 1989 after admitting having sex with the girl beginning when she was 14. Two years later, she got pregnant and gave birth. The diocese did not report DeShan to the police, and he was never prosecuted.

By 2002, he was working as a teacher in Cinnaminson when church disclosures about his past raised alarms. After a brief investigation, administrators allowed DeShan to return to the classroom, where he remained until last year, when a new generation of parents renewed cries for his removal.

The school board tried to fire him, citing both his conduct as a priest and recent remarks to a student about her “pretty green eyes.” In April, a state arbitrator ruled against the district, saying it had been “long aware” of DeShan’s conduct as a priest.

The state confirmed DeShan, who did not return calls for comment, still holds a valid teaching license, but that the licensing board is seeking to revoke it. Parents say he is not in a classroom this fall, but his profile remains posted on the school website and the idea he could be allowed back is troubling, said Cornell Jones, whose daughter was in DeShan’s class last year.

“When I found out about this guy being her teacher I was just, ‘No way _ there’s no way possible,’” Jones said. “I get a traffic violation and they make me pay. You violate a child and they just put you in a different zip code. How fair is that?”

The AP determined that one former priest had been licensed as recently as May. Andrew Syring, 42, resigned from the Omaha Diocese in November after a review of allegations that included inappropriate conversations with teens and kissing them on the cheeks. No charges were filed.

Dan Hoesing, the superintendent of the Schuyler Independent School DIstrict in Nebraska, said he could not disqualify Syring when he applied to be a substitute teacher because the former priest had not been accused of outright abuse or criminally charged. But Hoesing instituted strict rules requiring Syring to be supervised by another adult at all times, even while teaching, and banning him from student bathrooms or locker rooms.

Syring did not return messages for comment left with family members.

In many of the cases where a teaching license was revoked, the AP found the former priests went on to seek employment teaching English as a second language in private clinics, as online teachers or at community colleges.

“If these guys simply left and disappeared somewhere, it wouldn’t be a problem,” said Doyle, the canon lawyer. “But they don’t. They get jobs and create spaces where they can get access to and abuse children again.”

FILLING THE VACUUM

To a large extent, nonprofits, survivors groups and victims have stepped in to fill the void in tracking and policing these clergy members while they await stronger action.

Nojadera, with the bishops’ youth protection division, said more and more of his emails about priests are from concerned parishioners who are taking up the cause of protecting children.

“The lay faithful definitely seem to be stepping in,” he said. “Part of that is the awareness of the community in many ways based on the trainings we are having for our children and others in the parish communities.”

Gemma Hoskins, one of the stars of the documentary series “The Keepers” about abuse in a Baltimore Catholic school, also is taking up the cause.

Hoskins and a handful of volunteers have started a homegrown database using spreadsheets of clergy members created by a nonprofit called BishopAccountability.org to locate priests accused of abuse and post their approximate addresses.

“We’re careful. If their address is 123 Main Street, we’ll say the 100 block of Main Street like the police do,” she said. “We don’t want any of our volunteers to get in trouble, but it’s something all of us feel is necessary. If the priests are laicized, it’s even scarier … because it means the church isn’t tracking where they are living. They’re out there in the world as unregistered sex offenders.”

David Finkelhor, director of the Crimes against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire, said reports of abuse in the church have decreased and that all indications are that fresh allegations are being properly reported.

He also said that while keeping tabs on the accused abusers is important, the public shouldn’t assume all the former priests pose a big risk, noting that roughly one in every five child molesters reoffends.

“That’s lower than for a number of other violent crimes,” he said.

Still, he feels church leaders need to do far more to help track these clergy members, since anemic reporting in the past means little now prevents many of the priests from once again getting close to children.

“Tracking them is something they could have done as part of a general display of responsibility for the problem that they had helped contribute to,” Finkelhor said.

__

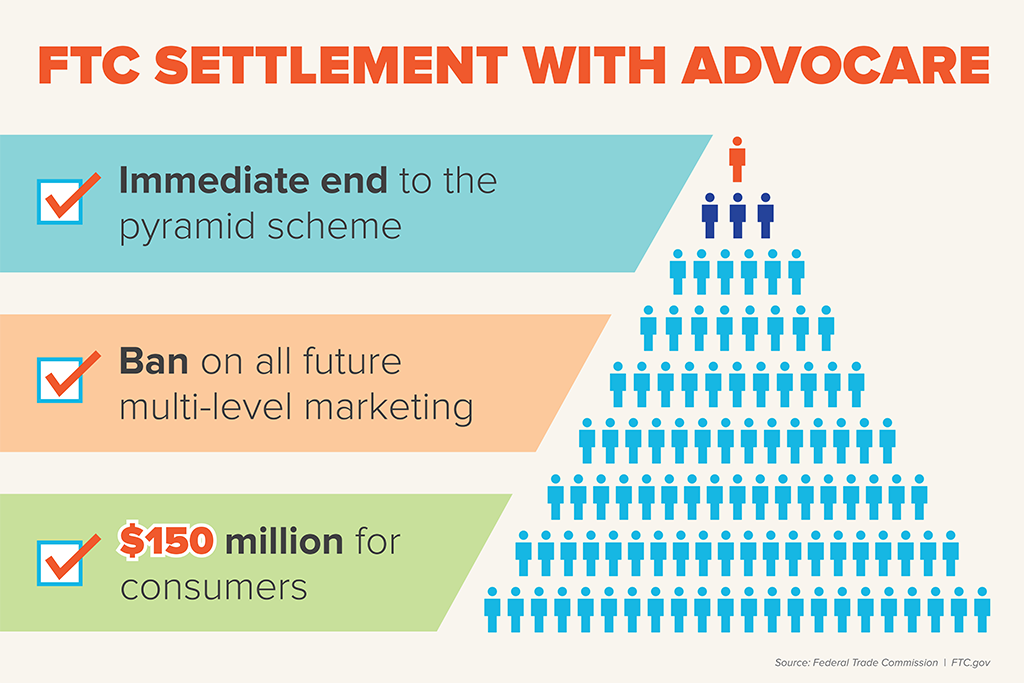

The FTC complaint filed in federal court also charges two other top AdvoCare promoters, Danny and Diane McDaniel, with unlawfully promoting a pyramid scheme, making deceptive earnings claims, and providing others with the means and instrumentalities to do the same.

The FTC complaint filed in federal court also charges two other top AdvoCare promoters, Danny and Diane McDaniel, with unlawfully promoting a pyramid scheme, making deceptive earnings claims, and providing others with the means and instrumentalities to do the same.